Spring 2024

Presbyterian Funerals - by John W Nelson

In this generation Presbyterian ministers are completely familiar with the process of taking funeral services, in the family home, in an undertaker’s “Funeral Home”, or in their own church or meeting house. Indeed funeral services in Presbyterian churches have increased greatly in numbers in the last 25 years. Until 200 years ago this was not the case.

Originally Presbyterians had a strong aversion to the idea of holding a service at a funeral. For them, this was too reminiscent of the pre-reformation Roman tradition, which they reacted against in every way possible. In the 17th and 18th centuries, in Ulster, the custom was for the minister, on being notified of a death, to attend in the family home and to read Scripture and offer prayer. Having brought consolation in this way, the minister would then leave. He would not attend the burial, which was a purely functional event with family and community conveying the deceased to the burial ground for the interment, after which the proceedings finished when the grave had been filled in.

However, some ministers felt a need to deliver an address to the assembled mourners and came to the conviction that a service in the meeting house would be appropriate on such occasions. The journal of Rev. A.G. Malcolm (minister of Newry 1809 – 1823) gives an insight into the beginning of these new developments in Irish Presbyterianism.

On 28th November 1812, a funeral service was, for the first time, held in the meeting house of Newry, before the interment of Mrs. Glenny, wife of Isaac William Glenny, one of the elders of the congregation. In August 1818, Rev. Malcolm pronounced an oration at the graveside for the first time, and he continued this custom, “though the funeral service in the meeting house is usually preferred”. Indeed, afterwards, he often repeated the address in church and at the graveside. By 1820, the precentor and choir were preparing special music for use in church funerals, so by then church funerals must have been fairly common. It is highly likely that these occasions, whether conducted by the minister in church and/or at the graveside, were amongst the first Presbyterian funerals in Ulster. It is only fair to mention however that for the next 150 years the great majority of Presbyterian funerals took place from the home of the deceased.

Malcolm’s journal makes mention of the pulpit being draped in black for memorial services of national significance. As the nineteenth century advanced that custom was followed for the funerals of Presbyterian ministers themselves and has continued into our own time.

Autumn 2023

A Black Sheep - by John Faris

My great great grandfather Rev James Glasgow pioneer Irish Presbyterian missionary to Gujarat, North India kept journals, the last one of which (1857 -1890) is my treasured possession. I am trying to transcribe it to a blog[1]. Every now and then a nugget appears:

1870 24 April It has been rumoured that my nephew the Rev James Glasgow Armstrong of St Louis Missouri has joined the Prelatic church in America. I am apprehensive that this may be true; as in a letter some months ago he spoke in apologetic terms of the prelatic system. May God lead him to knowledge of the truth.

“Prelatic” refers to the episcopal system of church government. His uncle did co-operate with Anglican missionaries, probably those of “low church” and evangelical outlook but he chronicles a conflict in Ahmedabad in the early 1860s with a “Puseyite”[2] army chaplain who prevented him from holding services in an army chapel. Glasgow attended one of the chaplain’s services and “heard a tolerably pretty nothing on 1 Cor 15.56, - a rich subject [?] surely.” It must have been intimidating to have the pioneer Irish Presbyterian missionary seated in the congregation.

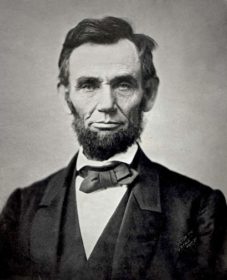

I googled Rev James Glasgow Armstrong and found his obituary from the St Louis Post in March 1891. It records his nephew’s colourful career: rumoured to be the assassin of Abraham Lincoln (they had fake news back then) and also disciplined twice, once for drunkenness and again for drunkenness and frequenting houses of ill fame, denied by him on both occasions. In addition his daughter created a sensation by deserting her husband on the morning after their marriage. “She is now on the stage.”[3]

Further googling produced speculations about him being John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of Abraham Lincoln and some more information about his career and final disgrace.[4] The theory was that Booth had not been killed on arrest but had somehow escaped to St Louis where he had presumably disposed of Armstrong and taken up his persona. Evidence was adduced that they looked alike, with a scar and a limp and that Armstrong was much interested in drama, giving lectures on Shakespeare in later life, as well as having a daughter “on the stage”. (Booth was an actor.) But Armstrong visited the old country in 1866 and 1881 and even if Booth had been able to deceive Americans, I don’t imagine Armstrong’s uncle and other shrewd Co Antrim relatives would have been deceived for long. (Unless he managed to persuade them to join the conspiracy …)

We should dismiss the Booth speculation, but Armstrong came under both Presbyterian and “prelatic” discipline, alcohol being involved on each occasion.

In 1867 when he was a United Presbyterian Church minister in St Louis “a charge of drunkenness was preferred against him by a member of the congregation, and he was tried by the Illinois Presbytery …and was found guilty and ousted. Then he was taken into the Old School Presbyterian Church and shortly afterwards accepted a call to Couteau Avenue Presbyterian Church. … The change from United Presbyterian to regular Presbyterian denomination was not so great, as the doctrines of faith of the two denominations are substantially the same, the principal difference being that the United Presbyterians sing the Psalms of David, as the Scotch Presbyterians do and are also opposed to membership of the Masonic and other secret orders.”

A couple of years later Armstrong joined the Episcopalian Church and was rector in different places until coming to Atlanta, where “he was charged with having visited a house of ill fame in Cincinnati and was found guilty and suspended for five years.” The obituary quotes an “intimate friend” who refutes the identification with Booth, as Armstrong was in St Louis at the time of the assassination. This friend also disputed the first charge of drunkenness and apparently as many as thirty members left the congregation and followed their ex-minister to his new charge. He also quoted a written explanation from Armstrong about the Cincinnati incident.

“He was on his way to New York for a summer vacation when he received a telegram from a relative to assist him in locating and recovering a daughter who had gone astray in Cincinnati … the two went to Cincinnati together and after visiting several houses of ill fame found the girl and induced her to return home. They did not visit the houses as clergymen, because that would have defeated their object. While they misrepresented their business there, they did not do anything else that they could be blamed for, and the cabman was mistaken in supposing them to have been intoxicated.”

That the sanction was a five year suspension rather than dismissal from office may suggest that the Bishop was somewhat sympathetic and wanted him to step back for the scandal to recede. But it is strange to have been accused falsely twice of being intoxicated. It was presumably during his suspension that Armstrong started his drama lectures. He died in 1891 before he could resume ministerial duties.

Thankfully his uncle had predeceased him in 1890, for not only is James Glasgow referred to in his nephew’s obituary as an “episcopal missionary” which he would not have appreciated given his opposition to “prelacy”, but he seems to have been ignorant of the shadows around his nephew - both the undeserved imputation of being Lincoln’s assassin and the more substantial and sad allegations to do with alcohol. As another great great grandson[5] has remarked “There is always one black sheep in the family.”—

John Glasgow Faris retired from ministry in Aghada and Trinity Cork in 2017. His father’s mother was a daughter of Glasgow’s youngest daughter, Harriet Acheson.

[1] http://revjamesmcclureglasgow.blogspot.com/

[2] Puseyite a reference to the “High Church” movement in Anglicanism, often known as the “Oxford Movement” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oxford_Movement in which E. B. Pusey (1800-82) was influential.

[3] https://www.newspapers.com/clip/13396935/st-louis-post-dispatch/

[4] http://hauntedohiobooks.com/news/11107/

[5] Mr Alastair Rankin

Welcome Back to Heritage - by Alison McCaughan

As a retired teacher, I am sometimes asked by strangers, “What did you teach?”

When I reply, “I taught, history”, I often get the response, “Oh dear. I hated history at school; it was all dates and lists and terribly boring. But, you know what? I am really interested in history now. I love finding out about my own area and I do wish that I knew far more Irish history.”

Leslie Clarkson, a former professor of history at Queen's University, Belfast has written, “History is important. We are what the past has made us, and what we believe the past to have been influences how we behave in the present. The purpose of doing history is to entertain, to instruct, and to enhance understanding of ourselves and the society of which we are part.”

Whilst most people would agree that history is important, the challenge is to make history accessible; and this is what the articles in Heritage aim to do. Our hope is that you will find articles that are entertaining and interesting, but also which will whet your appetite to explore our PHSI website further.

Raymond Gillespie has written that in every local area there are interests or things which draw people together and he gives the examples of family, social groupings, politics and religion. The latter, of course, includes Presbyterianism. In Ireland, Presbyterianism is complex and much has been written about the theological controversies within Irish Presbyterianism throughout the years. But Presbyterianism is also about the stories of the people who lived through traumatic times, who got on with living as well as they could, and found solace and comfort in their personal faith as they faced social, political and personal crises. It is hoped that Heritage will include stories about all the people, the great and the good, the conservative and the radical, the well-known and the little-known . . . and some rogues and rascals forby!

A Night to Remember - by Jim Stothers

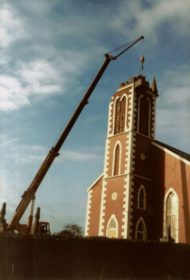

It was Sunday 19th December 1982 and my first Carol Service as Minister of St Johnston and Ballylennon in east Donegal. The service was in St Johnston church. There was a funeral in St Johnston graveyard that afternoon after which I stood at the foot of the church tower, just looking round at the gravestones, the people, and across the river to County Tyrone on a cold but calm day.

There was a minor controversy about the Carol Service. In my ignorance as a new minister I had arranged it for 7.30pm, not the traditional time of 8.00pm. Anyway, it was well attended and enjoyed by all. We sang nine carols altogether, beginning with ‘Silent Night’. It would turn out that it would be anything but a ‘silent night’! 1982 was an exciting year for us, with my installation in my first charge on 1 April, and the birth of the first of our three sons, Mark, on 15 October. Little did we realise as the service ended and I stood in the vestibule to shake hands with people as they left what was to happen a few minutes later. The last of us left at 8.40pm and I made my way over to the manse, just beside the church. It had started to rain quite heavily. Shortly after 9 o’clock I started to change two-month old Mark’s nappy – a cloth one, mind you, with safety pins – when suddenly there was a deafening bang. Smoke filled the house, and water started to leak from a pipe up on the kitchen wall. Oh, and the lights went out! I had been changing the baby on a mat in front of a coal fire, so was able to finish that job, but by now the smoke was making us choke. Where were we to go? It was pouring down outside, and you couldn’t breathe. The entrance hall to the manse was the answer. Dry, with fresh air – but the cold of a December night!

We weren’t sure what happened at first but it became evident that lightning had struck the church tower, travelled to the other end of the church, then across on the mains electrical wires to the manse where it blew up the fuse-board, and then jumped from the wiring into a copper pipe (the source of the water leak) to find an earth. The whole village of St Johnston had the electrical and telephone systems destroyed. We found shelter for the night and the next few days with one of the congregation’s elders, until power was restored and we were able to be back in the manse. Christmas was spent with my and Lynda’s parents in Belfast and Comber.

We weren’t sure what happened at first but it became evident that lightning had struck the church tower, travelled to the other end of the church, then across on the mains electrical wires to the manse where it blew up the fuse-board, and then jumped from the wiring into a copper pipe (the source of the water leak) to find an earth. The whole village of St Johnston had the electrical and telephone systems destroyed. We found shelter for the night and the next few days with one of the congregation’s elders, until power was restored and we were able to be back in the manse. Christmas was spent with my and Lynda’s parents in Belfast and Comber.

The manse was habitable again relatively soon but the church was wrecked, the most obvious destruction being that of the tower, but also the heavy lath and plaster ceiling came down in most of the length of the church from vestibule to pulpit. The Rt Rev Dr Tom Simpson as Moderator spoke at the re-opening service on 4 March 1984.

There were some remarkable, perhaps even providential things about that night. Firstly, a representative of the insurance company had inspected the church earlier that year in the summer and certified it – in writing – to be fully covered (even though there were no lightning conductors!), so there was little draw on the congregation’s financial resources. Secondly, the congregation raised funds for repairs anyway. So, when, after well over a year worshipping in the church hall, and it being realised that it was in serious need of refurbishment, there were funds to make a start on doing that and we ended up with a much improved building. And most importantly, my mistake on the timing undoubtedly saved lives. If the service had been at the traditional time of 8.00pm there would have been a large number of people still in the vestibule – and it had been totally wrecked by the large chunks of masonry that fell into it from the tower that night. A night to remember!

Heritage - a magazine that deals with history!

But please don’t let that frighten you. Sadly for many the thought of history revives old school nightmares of memorising names and dates. This is different. This is history as a story – HIS Story.

The idea of Heritage is to give you a flavour of the story of Christ working through His Church by retelling the story of past events and people, giving you information, or helping you find more information. In other words while we want to make the story more accessible, the main component in all of this is YOU. You are part of this story, just as your forebearers were and as you children will be.

The first issue of Heritage included

Hello and Welcome

PHSI Website

I didn't know that!

How God used a poor preacher

The Porter Family

What happens when people move away?

Discover more about the history of the Covenanters

A new beginning - History of Mullingar Presbyterian Church

Exciting future for the Society as new premises open

Make a start here to finding out something more about HIStory in Ireland.

The second issue of Heritage included

Hello and Welcome

The day the minister called

Creevelea Presbyterian Church

William Martin

Francis Makemie – the father of American Presbyterianism

Would you believe it?

The historic synods revisited

William Dool Killen

New Publication – Dr Tom Baker

The third issue of Heritage included

Hello and Welcome

Blackmouth

Ancient Baptismal Font

The Story of Revivals in Ireland

Something for Nothing!

Presbyterians in the Episcopal Church

The Days of the Mayflower

Lost and Not Found!

St Patrick a Presbyterian

New Publication – Sketches of the History of Presbyterians in Ireland 1803