Commander Francis Anderson Calder (1787–1855), RN,

Animal Welfare Supporter and Anti-Slavery Campaigner

Francis Calder is one of those lesser known Presbyterians in Ulster who made a significant contribution to humanitarian issues.

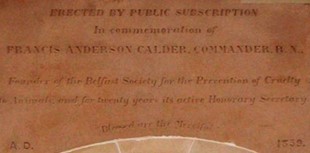

He was born in Edinburgh and as a young man entered the Royal Navy. He commanded various vessels during the Napoleonic Wars and resigned from the Royal Navy in 1815 with the rank of Lieutenant. An oil portrait by an unknown Irish artist of Commander Calder in full naval uniform is in the Ulster Museum collection but it is not clear when or why he was promoted to the rank of Commander. He is commemorated in Belfast by a memorial fountain with two cattle troughs at Custom House Square beside the quay along which cattle were once driven to market.

The Calder Fountain Memorial in Custom House Square, Belfast

|

|

|

(For more detail about the fountain memorial see - www.belfastentries.com/people/francis-calder-the-calder-fountain-memorial/)

He provides a good example of how humanitarians could be involved in different causes. He was a founder in 1836 of the Belfast Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (renamed the USPCA in 1891), the second oldest such organisation in the world after the London Society of 1824 (which became the RSPCA in 1840), and was its Secretary until his death. He taught in the Sunday School of the Belfast Charitable Society. He was also, with James Standfield, Joint Secretary of the Belfast Anti-Slavery Society. They allied themselves with the abolitionist Rev Isaac Nelson of Donegall Street Presbyterian Church.

They allied themselves with the abolitionist Rev Isaac Nelson of Donegall Street Presbyterian Church. Calder’s experience as a seaman may have helped to make him concerned for animal welfare. He saw how livestock shipped to Belfast were often left without enough food and drink and at his own expense he provided water troughs in various parts of the town to relieve their suffering

The connection between the campaign for animal welfare and the anti-slavery campaign does not seem yet to have been fully explored. Leading supporters of animal welfare such as Fowell Buxton, Lewis Gompertz, Richard Martin (‘Humanity Dick’) and William Wilberforce were also prominent campaigners against slavery.

In 1845 and 1846 the Anti-Slavery Society welcomed to Belfast one of the leading American abolitionists, the fugitive slave Frederick Douglass, and Calder facilitated his speaking tour. Unlike many Irish Presbyterian clergy of the time Calder agreed with the criticism by Douglass of the Free Church of Scotland which Calder termed the “semi slave church” (Ritchie. p. 109), for having accepted funds from American slave-owners. Although a number of Presbyterian ministers welcomed the denunciation of slavery in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) (Ritchie, p, 114), Calder grew increasingly despondent about the prospects of slave emancipation, and in October 1853 he and his colleague Standfield resigned as Secretaries of the Belfast Anti-Slavery Society, unhappy at how Belfast Presbyterians viewed the Free Church of Scotland (Ritchie, p. 115). Indeed already in April 1853 Calder had remarked that Belfast was “practically a dreadful proslavery town” (Ritchie, p 115.)

Calder was himself a Presbyterian, a member of the College Square congregation. He would not have had far to go to church—just a five-minute walk along Durham Street from his home at 5 College Street South (now Grosvenor Road). The church building, which was on the corner of Durham Street and College Square North, was demolished for road-widening in 1966. Calder was ordained there as an Elder on 5 October 1849. The Minister of the congregation from 1847 to 1864 was Rev Joshua Collins. As a member of a small Kirk Session in an inner-city church Calder may have been kept busy, but he did not serve long in that capacity. He died on 7 November 1855 and was buried in the Shankill Graveyard. His reputation as a good man lived on. Mary Ann McCracken (qv) who is today probably the most famous Belfast opponent of slavery, recalled in a letter to Dr RR Madden dated 2 August 1859 that Calder had been among the few people in Belfast to have kept up the practice of abstaining from goods produced on a slave plantation, and she referred to him as “one of the most perfect of human begins [beings]” (McWilliams, p.797). It had been another Presbyterian, Dr William Drennan (qv) who had formulated the original Irish abstention pledge back in 1792 (Rodgers. p.190). But it was not until seven years after Calder’s death, and in the course of the Civil War, that Abraham Lincoln proclaimed the emancipation of slaves in the rebellious American states.

Suggestions for further reading:

Daniel Ritchie, Isaac Nelson: Radical Abolitionist, Evangelical Presbyterian and Irish Nationalist (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2018). Ritchie has drawn extensively on Calder’s papers in the Bodleian Library, Oxford (By far the most authoritative account of Calder’s abolitionist activity but he does not examine Calder’s work for animal welfare.)

Whyte, Iain, ‘Send Back the Money!’: The Free Church of Scotland and American Slavery (Cambridge: James Clarke & Co, 2012).

Fenton, Laurence, Frederick Douglass in Ireland: ‘The Black O’Connell’ (Cork: The Collins Press, 2014).

McWilliams, Cathryn Bronwyn, The Letters and Legacy of Mary Ann McCracken (1770-1866) (Åbo, Finland: Åbo Akademi University Press, 2021).

Rodgers, Nini, Ireland, Slavery and Anti-Slavery: 1612-1865 (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007).

The Tree: The Centenary Book of the Ulster Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals 1836-1936 (Belfast, 1936) – ‘Historical Sketch’ by Florence Moore Holmes.

We gratefully acknowledge Dr Colin Walker for permitting the Presbyterian Historical Society of Ireland to publish his article on our website.